Government by Greed: PART 2: Role of the Fiji Military

By Guest Writer-Subhash Appana

The

British system of running the military with a class structure and inbuilt

systems of discrimination became accepted practice. That’s partly why Indian

demands for equal pay to join the military after 1939 was seen as treachery.

Selective

recruitment had already been established as part of the Native Constabulary

where loyal eastern Fijians (as opposed to westerners) had privileged access

and Indians did not feature at all. Later Indians were barred through elaborate

physical requirements of height and weight. This, after Indian troops from the

sub-continent had already shed 85,000 lives for the Crown and Churchill had

described them as “splendid fighting men”

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Role of the Fiji Military

The last Greed article focused on the Fiji Military and

how it evolved from the Royal Army of Ratu Seru Cakobau that was used to

subjugate renegade tribes in the highlands of Viti Levu, to the Armed Native

Constabulary that confronted Indo-Fijian worker strikes, to the Royal Fiji

Military Forces that saw Fiji through independence in 1970. Just what was the

role of the RFMF in the independent, democratic sovereign state of Fiji was

either deliberately or conveniently left unclear at that juncture.

Going back to Fiji military participation in the two

world wars on behalf of Bolatagane

(or Land of Men) and empire, WW1 (1914-18) was waged for “democracy”. The same

happened in WW2 (1939-45) with its focus on thwarting fascism. And during the

Malayan Emergency (1948-60), the enemy were communist insurgents who again

presented a threat to democracy. Ironically, while these manly international

campaigns were being waged for “freedom” and “democracy”, leaders in Fiji were

totally unconcerned about the pleas of Fiji’s very own semi-slaves, THE

GIRMITIYA.

Another, more insidious, military reality of the time

involved the establishment of a white officer-class and a 2-tier system of pay

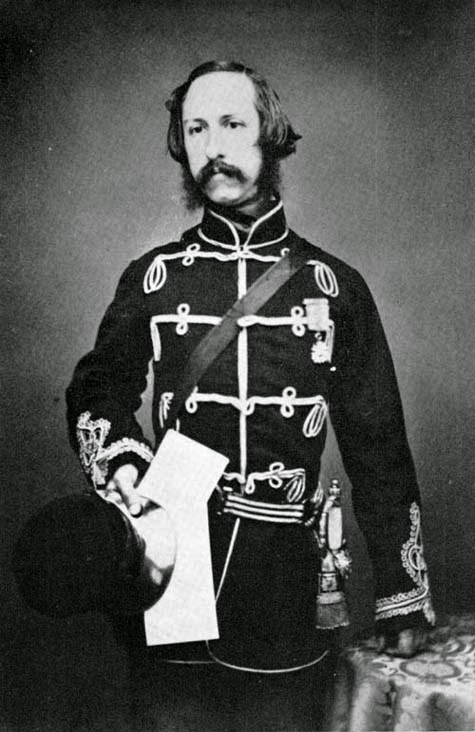

and discriminatory recruitment into the military. Ironically Fiji’s most distinguished

son, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, joined the French Foreign Legion because of this

very same discriminatory recruitment in the British Army – Ratu Sukuna was refused entry into the British Army.

|

| British Army was an epitome of discrimination. Fiji's proud son and military leader, RATU SIR LALA SUKUNA, was refused entry in the British Army, so he joined the French Foreign Legion. |

At independence in 1970 Fijian troops had thus participated

in 3 major British military campaigns on behalf of democracy, but were never

really apprised of its mechanics and implications. The British system of running the military with a class structure and

inbuilt systems of discrimination became accepted practice. That’s partly why

Indian demands for equal pay to join the military after 1939 was seen as

treachery.

Moreover, selective recruitment had already been

established as part of the Native Constabulary where loyal eastern Fijians (as

opposed to westerners) had privileged access and Indians did not feature at

all. Later Indians were barred through elaborate physical requirements of

height and weight. This, after Indian troops from the sub-continent had already

shed 85,000 lives for the Crown and Churchill had described them as “splendid

fighting men” (Mason 1976, Perry 1988).

Thus at independence the RFMF was loaded with eastern

Fijians or those loyal to their chieftainship, had a predominance of chiefs at

its apex, was not sure about its role within the democratic framework, and had

ominous confusions about its loyalties vis a vis central government and the

carefully nurtured chiefly system, which was always in effect, a shadow

government.

It was contended in the last Greed article that the RFMF and the Fiji government were

expected to be linked forever through chiefly control of both institutions.

This was supposed to ensure military support for government at all times. Thus

in the initial post-1970 scheme of governance (and politics), the RFMF was supposed

to be a silent partner that could be called on at any time should the need

arise. There were a number of problems with the assumptions underlying that

model of governance.

Firstly, Fijian

unity under the chiefly system was never guaranteed. Fiji was not alone in this

regard as many other traditional societies continued to be challenged through

the expansion of the paid economy and its links with modern education. The

post-independence Fijian government attempted to slow the ravages of this

process through an elaborate system of patronage within the civil service, but

this lacked capacity and burst at the seams down the line.

|

| RATU SIR KAMISESES MARA never envisaged the Alliance or the Eastern Chiefs to lose power. Advance indication of this was his loss in 1977, and later the loss in 1987 which resulted in Rabuka's coup. |

In quick-time the

very non-democratic doctrine of Fijian specialness that ensured Fijian unity

found itself at loggerheads with the democratic doctrine of multi-racialism.

This was the biggest problem Ratu Mara faced in the run-up to the 1977

elections. His main split with Koya came after he declared special access to

scholarships for Fijians in 1975. Hard at his heels was also the hound of

Fijian nationalism expounded stridently by firebrand Rewan, Sakeasi Butadroka.

The April 1977 elections was thus shockingly lost by Mara and the Alliance

Party because of a significant (30%) split in Fijian votes.

And while the NFP

dithered on presenting SM Koya as PM to Governor General Ratu Sir George

Cakobau, rumblings were clearly heard in little gatherings of forcing a

takeover. In fact, part of the prolonged disagreement within the NFP also

featured concern about how the RFMF would react to an Indian PM. The military

option however, paled into insignificance as AG Sir John Falvey and others

found a constitutional escape to form a minority government.

Ratu Mara was back

as PM, the status quo prevailed and all was well again in God’s Fiji as the NFP

hemorrhaged and the Alliance swept into power in the subsequent September 1977

elections. A serious concern however, had been verbalized: could the Fiji Army be relied on to remain neutral in the event of a

win by a non Fijian Establishment-backed political party. On the other side

of the political spectrum, glimpses had been seen of the role that the military

could play in correcting the perceived injustices of a foreign system of

governance – democracy.

The RFMF was thus

seen as the last line of defence for the Fijian traditional system of

governance and all that it entailed at that point in time. In fact expectations

in this regard began to mount as the next elections loomed. In 1982, as

election fever heated up, the nuclear component of the cold war swept the

Pacific, and Fiji for the first time saw a foreign dimension in its elections

as amid much acrimony and accusations the Alliance returned with a drastically

slimmed margin.

After 1982, it was

clear that the Alliance Party was walking a tightrope. There were increasingly

visible criticisms of the Mara government among Fijians, the patronage system

of the 1970s had outgrown its capacity, and very importantly, the economy was in

contraction mode. As government began to take forced unpopular decisions, the

masses began to experience shared hardships.

A commonality of

concerns and problems across the carefully established ethnic divide was thus

developing in Fiji in a belated manner because it was blocked through selective

policies earlier. If the 1970s presented a decade of euphoria and complacence,

the 1980s demanded a hard look at reality, democracy and the ballot box. It is

this that would finally force the military card in Fiji’s politics

Stay tuned Part 3: Power

in Perpetuity or Coup

It is no secret that the architects of the

1970 constitution, apart from the Indian delegation, envisaged power in

perpetuity for the Fijian Establishment-backed Alliance Party of Ratu Sir

Kamisese Mara…..

Democracy

in Fiji was thus meant to ensure power in perpetuity to the Alliance Party and

no one could really expect any different for the country. The role of the

military as a protector of this shakily established façade of democracy was

therefore, always open to revolutionary introspection – Rabuka’s coup should

not have been such a big surprise.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[About the

Author: Subhash Appana is an Indo-Fijian academic

with Fijian family links. He was brought up in the chiefly village of Vuna in Taveuni and is

particularly fond of the Fijian language and culture. Subhash has written

extensively on the link between the politics of the vanua, Indo-Fijian

aspirations and the continued search for a functioning democracy in Fiji. This

series attempts to be both informative and provocative keeping in mind the

delicate, distractive and often destructive sensitivities involved in

cross-cultural discourses of this type.]