Government by Greed - PART 5: 1987 - The

Impossible Coup

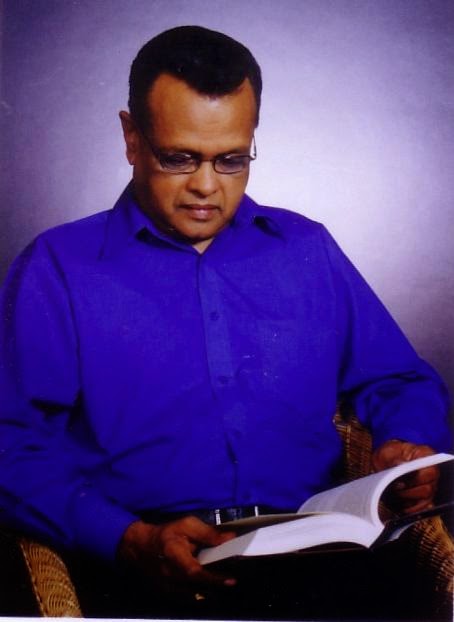

Guest Writer-Subhash

Appana

A political

coup-de-tat has few civilian parallels in terms of rationale, planning,

logistics, back-up support, follow-up and consequences. In Fiji, the unthinkable

had happened at the April 1987 elections – the carefully camouflaged and

internally inconsistent myth of democratic power in perpetuity was finally

blown. First there was disbelief, then consternation, then

confusion followed by complaining and anger. It is at this point that the

coup-makers stepped in to provide guidance to a relatively small portion of the

country that appeared to be

reeling like a plane without a pilot.

The message that

these saviours brought was not about democracy and the inevitability of changes

in government, but on how the Fijian people were under threat from the greedy,

dishonest and covetous designs of the “kai Idia” or the Indians. This was an

old message that had potent political traction and it became the mantra that

rallied the masses. Local reggae band Rootstrata,

came up with a stirring number about Fijian self-determination, the Fijian way

– ‘o cei o ira (who are they), they sang. There was thus no other way for Fiji

at that juncture.

Rabuka clearly

stated this in his (now oft-questioned) book, “No Other Way”. Of course if the

Fijian leaders, especially the traditional ones had spoken up and stemmed the

tide, coup might have been avoided because the rationale for it would have been

nipped – no disturbance, no need for coup! The problem was, this was very

difficult and it did not leave (or create) room for a re-look at Fiji politics

in order to change it and make it more appropriate to the changing times.

Bavadra & Co were hardly likely to re-think a model that had just brought

them to power.

There was a more

significant development within those orchestrated disturbances that has so far

been given scant notice by analysts of the 1987 coup and Fiji politics. The

framework within which the disturbances were unleashed involved a cadre of

fiery, reactionary, peripheral leaders, who had been agitating for public

recognition, as front men. Behind this frontline was a group of shady

“controllers” who, in turn, were following directives from a high command. The

public only got to see the “faces” and has continued to speculate about the

“non-faces”.

More importantly, at

some stage the rebellion acquired a momentum and direction of its own. The

front-men, who were supposed to follow directives and exit centre stage when

required, suddenly had too much power, energy and ambition. Taniela Veitata,

Manasa Lasaro, Jona Qio, etc. began to plan and make independent

pronouncements. Those who were supposed to be under control were suddenly out

of control. That’s where the 1987 coup went wrong, and that’s what Fiji is

still reeling from today.

Coming back to the

planning of that coup, the plotters needed backing from a number of quarters.

Firstly, they needed a smattering of lower-level traditional leaders – there

was no shortage of these. Then they needed leaders in an urban setting. And of

necessity, this included peripheral unionists, churchmen and thugs. All those

whose political (and therefore, economic) ambitions had somehow been kept in

check by the Mara government suddenly sprang to centre stage.

This was the

opportunity they had been waiting for and they made the most of it while

chanting the potent mantra of “down with the kai Idia”. Defenders of the Fijian

heritage suddenly sprang up all over the place as the fever took hold and

rebellion gained momentum. Many supporters joined simply for want of nothing

better to do, many were drawn by the power of the preachers and the occasion

that was created. Many thought they were really defending the Fijian heritage.

Many expected fallouts and were already fingering Indian houses that they’d

move into.

That was the nature

of the rebellion that preceded Rabuka’s coup.

A second, more

important concern that troubled the plotters of that coup was what would happen

afterwards. For an orderly transition from the brink of created chaos, they

needed to fall back on Fiji’s main leaders who commanded traditional Fijian

backing – they needed leaders who could control both the masses as well as the

keepers of the law (police and military). This meant they had to have the

support of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau and Ratu Sir George

Cakobau. These three leaders stood at the pinnacle of the Fijian chiefly system

ie. the traditional power structure at that point in time.

|

| The original Coup-maker-Sitiveni Rabuka, who has now gone into oblivion, and the coup culture he opened up in 1987 still affects Fiji. |

The Fijian

traditional administrative system that was shaped and fossilized by Governor

Arthur Gordon after cession in 1874 has the country divided into 14 provinces

which are in turn grouped into 3 confederacies – Kubuna, Tovata and Burebasaga.

Each of these confederacies is headed by a paramount chief. In 1987, Kubuna was

headed by ex-Governor General Ratu Sir George Cakobau. Tovata was headed by the

then GG Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau. And Burebasaga was headed by Lady Ro Lala

Mara, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara’s wife.

Ratu Sir Kamisese

Mara was thus not a paramount chief in his own right, but he was the husband of

one. On top of that, he had been groomed for and headed the modern structure of

government that was essentially juxtaposed on the traditional structure.

Moreover, Ratu Mara had been earmarked to lead Fiji by Fiji’s most prominent

colonial-era chief, Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna. In fact it was Ratu Sukuna who played

cupid in helping hitch Mara with the young lass from Burebasaga who would later

become the Roko Tui Dreketi, the paramount chief of Burebasaga.

|

| Former Roko Tui Dreketi, Adi Lady Lala Mara with husband Ratu Sir Kamiseses Mara. It is said that it was Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna who was instrumental in helping Ratu Mara wed Adi Laldy Lala Mara. |

The coup plotters of 1987 had to prepare to contend with the expected fallout after Rabuka executed his Treason at 10. Fiji would be rudderless and leaderless amid the vacuum that would be created by removing the Bavadra government. The trouble-makers were mainly urban Fijians who had been harnessed for the disturbances. They could be controlled by their newly-created leaders up to a certain extent only. The main source of stability had to come from traditional sources – the paramount chiefs.

And the 1987 coup did have either explicit or implicit

support from this all-important source as without military and chiefly support

a political coup-de-tat was not possible in Fiji at that point in time.

Next, how could this be true? Keep tuned, coming in

Part 6:

“…….. force and

violence are necessary complements of any coup-de-tat. And in order to “build”

the scenario to justify a coup, an orchestrated process is activated. The aim

is to create a situation that allows a treasonous, yet quietly-supported,

coup-maker to say “there was no other way”. This is exactly what happened in

Fiji, and that is exactly what Rabuka said after he executed the Father of All

Coups on 14th May 1987. The common thread that bound all who

supported that coup was the perceived need to protect the Fijian heritage and

save the Fijian race from Indo-Fijians.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

[About

the Author: Subhash Appana is an

Indo-Fijian academic with Fijian family links. He was brought up in the chiefly village of

Vuna in Taveuni and is particularly fond of the Fijian language and culture.

Subhash has written extensively on the link between the politics of the vanua,

Indo-Fijian aspirations and the continued search for a functioning democracy in

Fiji. This series attempts to be both informative and provocative keeping in

mind the delicate, distractive and often destructive sensitivities involved in

cross-cultural discourses of this type.]